Ethiopian Madonna

One very striking picture on the main stair at Campion Hall is a large Ethiopian icon of an enthroned Madonna and Child, the gift of Evelyn Waugh. There is a distinctive Ethiopian tradition of Christian art, of which this is a fine example. Ethiopia has been a Christian country for at least as long as the Roman empire. The legendary origin of Ethiopian Christianity is the conversion of a learned and pious Ethiopian eunuch by the apostle Philip in the first century AD (see Acts 8:26-38). However, archaeological evidence suggests that Christianity spread after the conversion of king Ezana during the first half of the 4th century BC. The earliest Ethiopian illuminated manuscripts, the Garima Gospels, were composed close to the year 500, and illustrated with evangelist portraits and illuminated Eusebian canons, in a broadly Byzantine style.

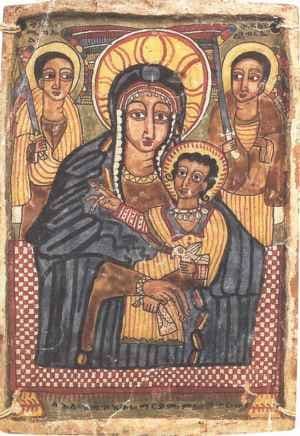

Apart from these spectacular early survivals, a fair number of medieval Gospel books survive from as early as the thirteenth century. These books are often quite lavishly illustrated with scenes such as an Annunciation, or images of the Virgin and Child as well as evangelist portraits. The earliest surviving Ethiopian icons also date to this period. Campion Hall has a small icon of the Holy Trinity in the icon room; provenance unknown. This has the form traditional in Ethiopian representations of the Trinity, as three identical bearded men, with the bright colours and lack of modelling typical of Ethiopian painting.

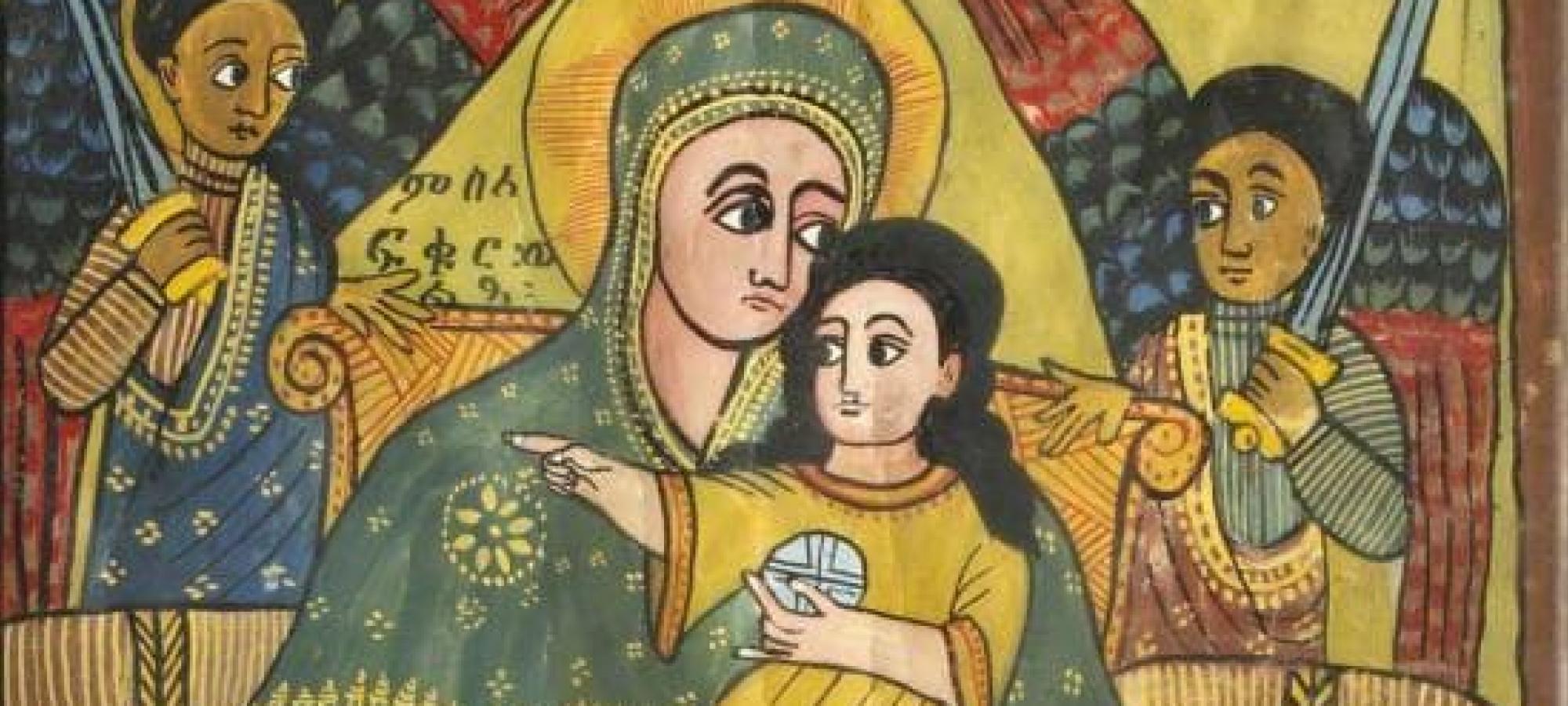

The Ethiopian iconography of the Virgin and Child draws on the Byzantine iconic tradition, going back at least to the sixth century in which the Virgin is enthroned and flanked by two angels. One distinctively Ethiopic figure is that the angels in our icon are armed with swords, a feature of other Ethiopian treatments of this theme; in Greco-Roman images, the angels stand at her either side in much the way that an empress would be accompanied by an honour guard of eunuch courtiers, and their open hands invite the onlooker to marvel at the throned queen. Further, an inscription in Ge’ez, the liturgical language of Ethiopia, identifies the figures as ‘Holy Michael, Holy Gabriel, with the Holy Child’: in Byzantine images, the angels are generic figures. The two bulging forms on either side of the seated Virgin represent the bolsterlike cushion often shown in Byzantine images of enthroned dignitaries. She wears a green maphorion, a garment covering the head and shoulders, mentioned in documents from the fourth to sixth century, and shown in, for example, the famous sixth-century mosaic of the empress Theodora and her ladies at Ravenna. Beneath this is a magnificent blue mantle, and beneath that, a brown dress. The child is extending his left hand in a gesture of blessing, and holding an orb in his right. One very curious feature of this image is the cloth or handkerchief held in the Virgin’s left hand. This is quite common on Ethiopian depictions of the Virgin and Child, but is not a feature of early Byzantine icons with this theme. However, there is, more generally, a principle that holy objects are handled with covered hands, which may account for it: in the earliest Orthodox icons of St Symeon the God-Receiver, he holds the Christ Child with a cloth over his hands. A second inscription in Ge’ez at the base of the icon reads ‘Hear my prayer, and let my cry come unto thee’.

Evelyn Waugh first visited Addis Ababa to report Emperor Haile Selassie’s coronation in 1930. Five years later, he returned to the country when he was appointed the Daily Mail’s Addis Ababa correspondent in 1935 to cover the Italo-Ethiopian war of 1935-6, a conflict which attracted worldwide attention since many feared that it would be the prelude to another world war. For Waugh, it was an experience which led to his writing his satirical masterpiece, Scoop, published in 1937. Far from writing despatches from the front line, as he had hoped, he found himself marooned, with other European journalists, in Addis Ababa. As he wrote to his fiancée, ‘the only news we get comes on the wireless from europe via Eritrea. No one is allowed to leave Addis so all those adventures I came for will not happen. Sad. Still all this will make a funny novel so it won’t be wasted.’ In fact he also got a non-fiction book out of his experiences, Waugh in Abyssinia (1936). It was during this conflict that he sent the image back to Fr. D’Arcy at Campion Hall, which was then still at Middleton Hall in St Giles’.

Waugh had a close relationship with Fr D’Arcy, who had received him into the Catholic Church: it was D’Arcy who suggested writing a life of Edmund Campion to Waugh in 1934. Waugh offered all future royalties on this book to the Hall, and Campion’s Liber Benefactorum reveals frequent entries of large donations from Waugh. It is unsurprising, given this context, that Waugh should have thought to pick up a piece of Ethiopian Christian art as a gift to Campion Hall while he was stuck in Addis Ababa with nothing to do.

It seems most probable, given its excellent condition, that the image dates from the first half of the twentieth century, though if so, it seems a little archaic; from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, Ethiopian religious painters typically began to model faces and limbs with shading to create an illusion of volume, which is completely absent in this image, though on the other hand, the large eyes suggest a relatively late date. The ground of the image is probably vellum, and the medium powdered natural pigments bound with animal-skin glue, which creates a tough yet flexible surface. Traditional painters used indigo for blue, and a mixture of indigo and orpiment for the green which is a striking feature of this image. Red was made from cinnabar, yellow from orpiment, and while browns were either earth colours, or a mixture of cinnabar, gypsum and charcoal.

Detail of traditional Ethiopian Trinity from Campion Hall (Icon Room)

Detail of comparable Ethiopian madonna, with handkerchief

Detail of comparably Ethiopian Trinity