Revd Dr Nicholas Austin, SJ delivers University Sermon on the Sin of Pride at Balliol College

On Sunday 24 November, the Master at Campion Hall was at Balliol College to deliver the University’s annual Sermon on the Sin of Pride. The sermon was endowed in 1684 by William Master who had been a fellow of Merton College. Administered by the Committee for the Nomination of Select Preachers this is one of several endowed sermons given each year. In this year’s sermon Fr Nick reflected on Augustine’s consideration of the doctrine of Original Sin and the goodness and grace of having been created.

The full sermon appears, below.

A University Sermon, Preached in the Chapel of Balliol College, 24th November 2024.

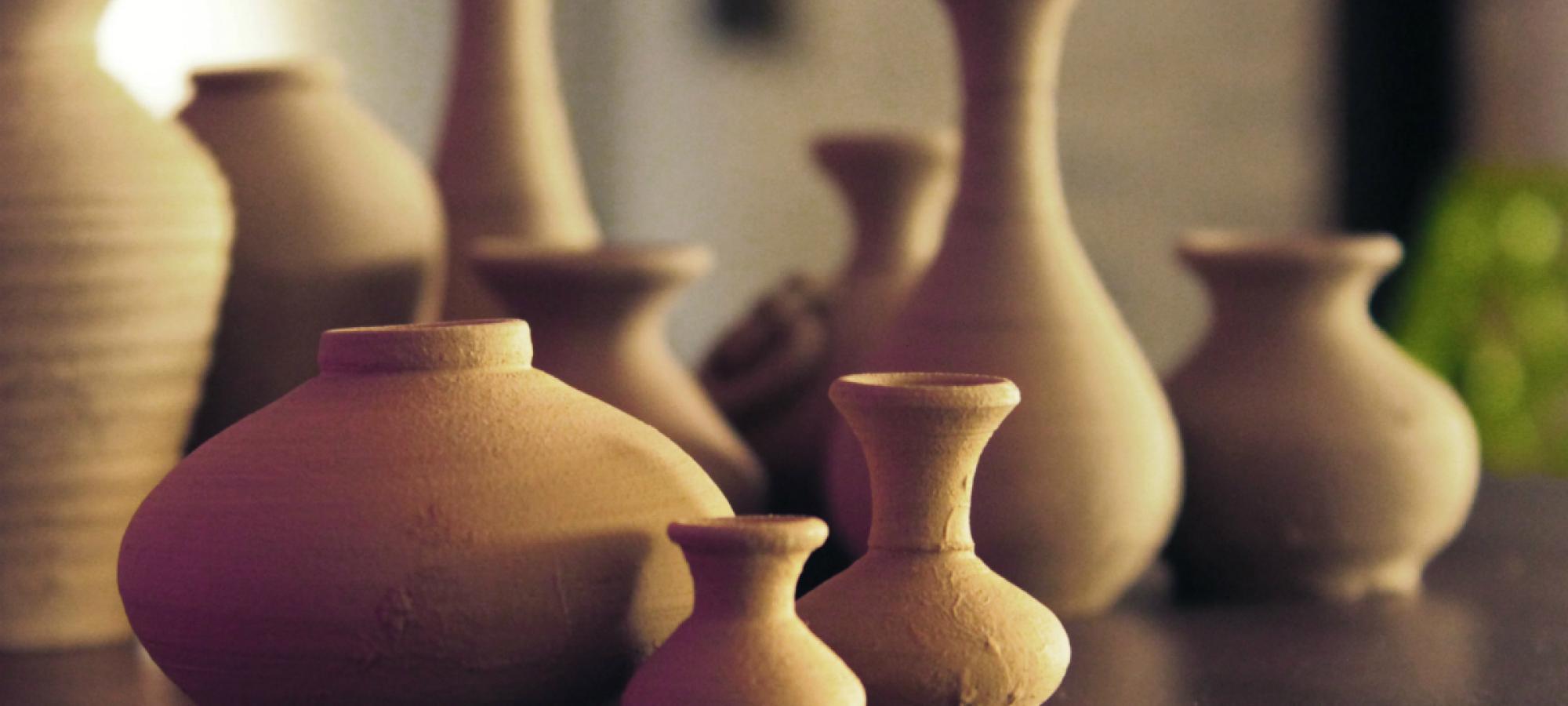

‘We have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us.’ (1 Corinthians 4:7)

My thanks to the Master, the Chaplain, and the community of Balliol College for your hospitality and for hosting this year’s University Sermon on the Sin of Pride. A curious topic for an annual University Sermon, the Sin of Pride. ‘None of that here in Oxford…. The greatest University in the World.’ Nevertheless, we find ourselves in debt to one Revd William Master, whose legacy in 1684 included the princely sum of five pounds to establish for Oxford an annual Sermon on the Sin of Pride, on the Sunday next before Advent, that is, today.

A modern congregation may well question what our friend the William Master took for granted, that there is such as thing as the sin of pride. Today, groups that have been victims of discrimination celebrate their identity with pride, as in black pride or pride month. And what is wrong with the honest pride in a job well done? In a weak moment, I wondered if I could use a well-worn undergraduate strategy, deftly using the set topic as an occasion to talk about a related one, about which one might have more to say. Could I not use ‘the Sin of Pride’ to talk about the opposite, namely, the virtue of humility? Sadly no. It turns out that the Revd William Master’s five quid stretches impressively to another annual University Sermon, to be preached on the Sunday before Lent, on just that topic, the Grace of Humility. Already bagsied by another preacher. So I shall stop wriggling and stick to the script: not the virtue of humility, nor even the virtue of pride, but what it says on the tin, the Sin of Pride.

If you have ever tried to remove a weed from your garden, you will know that you can cut it down as often as you like, but unless you dig it out, roots ’n’ all, the weed will relentlessly spring up again. Throughout history, believers have found sin to be like a weed with a deep tangle of root life, hidden from plain sight and difficult to uproot. Originally eight malignant roots were identified, the eight ‘evil thoughts’ named by Evagrius of Ponticus, an ascetic desert monk, in the fourth century. By the time time of Pope Saint Gregory the Great in the sixth century, pride had disappeared from the list, leaving only seven. Vainglory, envy, wrath, sloth, gluttony, lust, and avarice. The Seven Deadly Sins. From these sins, all the rest follow. So why did pride get dropped from canon? Is this because pride was considered less potent than the others? Quite the reverse. While the seven deadly sins are the springs of all other sins, pride is the ‘queen of them all’, as Gregory puts it. The concept of pride is therefore a serious piece of depth psychology, an investigation of the subterranean source of sin. Pride is nothing less than the the root of the roots of human evil.

A modern audience, again, is likely to read this tradition with suspicion. Preaching the evils of pride and the virtues of humility: is this not a way for the powerful to keep the oppressed in their place? At its best, it is precisely the opposite: a way to humble the oppressors. Take, for example, the sentiments of one Michael McCarthy, for 15 years the Environment Editor of the Independent Newspaper. Despite having long drifted from the Christian faith of his youth, as he retired from his role he surprisingly recurred at the last to the theme of Original Sin. ‘You may think,’ he says , ‘of the idea of The Fall as simply the story of Adam eating the forbidden fruit. But such a myth is not of itself what has gripped some of the most powerful minds in history. Rather, the idea of fallen Humanity gives potent expression to that prominent part of the human character which has been observed, down the ages, with horror: our terrible potential for destruction, for causing suffering to others and, indeed, now, for destroying our own home’. The words of an environmentalist. Since the Enlightenment, the dominant worldview has shied away from the idea of human nature as Fallen, confident that science, technology, education, and democracy will inevitably result in continuous progress for humanity. Yet the deep root of the roots of human evil, it seems, is not so easily uprooted. As humanity hurtles in full knowledge and freedom towards destroying the very conditions of its own life and flourishing, the doctrine of Original Sin appears not so much a quaint piece of religious myth as something sadly bordering on empirical fact.

We all know the story: Adam and Eve and the apple and the serpent. But for centuries theologians puzzled over the central question: What precisely is Adam’s sin, the Original Sin, the one that leads to the Fall? Is it the gluttony that wants to taste the juicy apple? Or is it disobedience, transgressing the puzzling command of the Lord not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil? A sophisticated audience who has read Sigmund Freud may see there the sin of lust. Or could it be, as Bernard of Clairveaux speculated, the vice of vain curiosity: what’s the harm in just looking, or having a taste, just to see what it is like? But it is to an African theologian, the greatest of theologians, one Bishop of Hippo, that we owe the precise answer to this riddle. Saint Augustine nails it when he names Adam’s sin, the Original Sin, not as disobedience, or gluttony, or lust, or even vain curiosity, but as the craving for undue exaltation of self. The Sin of Pride. For if you eat of the tree, the serpent tells Adam and Eve, ‘ye shall be as gods’.

As Michael Himes observes, it is unfortunate that Adam and Eve, in Chapter 3 of Genesis, did not share with us the advantage of having read Chapter 1.1 Had they done so, they would have noticed that they were already like God. What a wonderful affirmation of the dignity of the human person. The human person is created in the divine likeness, nothing less than imago Dei, the very image of God himself. But enter the serpent, who slyly plants a seed of doubt: you’re not like God, Adam, Eve, but you can become as gods if you but reach out your hand and seize it for yourself.

Pride, for Augustine, is therefore just this: the willful refusal to be a creature.2 After all, it is not an easy thing to accept to be a creature. It means being born into dependence on one’s parents, undergoing the trials of growing up, enduring the pains of labour, coping with the worries of making one’s way in the world, suffering the hurts and risks of relationship, accepting the suffering of bodily illness and injury, and, at the last, facing the inevitability of loss and death. No wonder we are in flight from our own creatureliness. No wonder we anxiously crave control over ourselves, over others, over nature. No wonder we fall, again and again, for the serpent’s lie, ‘take, eat, and ye shall be, not creatures, but as gods’. As Himes points out, the irony is that God has been trying to tell us from the very beginning there is a gift and a grace in being a creature. For on the sixth day, God saw that what he had created was not just good but very good. And while proud Adam has been in a mad sprint to become god, the humble God himself has quietly decided to become human. What deeper affirmation of the goodness of being a creature could we imagine?

‘Those who exalt themselves shall be humbled, but those who humble themselves shall be exalted.’ Augustine knew this saying of Jesus as a truth inscribed in his heart. We hear the story in the Confessions, how Augustine reaches an insoluble problem in his own life, a tangled knot that neither he, nor anyone he knew, could untie. Only when he gives up trying to solve it himself, throwing his body to the ground in tears in the garden, does he find himself lifted up by grace.

So we need not be so puzzled, I think, that our good friend the Reverend Bill Master asked the University of Oxford, once a year, to reflect on the Sin of Pride. A well-invested fiver after all. The University’s motto is Dominus Illuminatio Mea, the Lord is my light, my illumination, my enlightment. I have heard it said that this motto is ‘of its times’. But we need not be so proud as to think that our own times have nothing to learn from times past, when the motto was coined. Dominus Illuminatio Mea. The Lord is the source of our light, our illumination, our knowledge. We ourselves are not the light. For we are not as gods, but creatures, and what we have, we have received, as gift, and are in turn to pass on, as gift. As scripture says, ‘it is the God who said, “Light will shine out of darkness,” who has shone in our hearts to give the light of … knowledge... But we have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us.’ Amen.