![Altar Rails of St Charles Borromeo [formerly St Ignatius] Antwerp, American grain plants mixed with the expected what and grapes. The prologue to the book asks what the nodal Antwerp Jesuit community knew about Asia and the Americas.](/sites/default/files/styles/banner_2000x700/public/2024-09/Image%204_.jpg?itok=jP8QRY41)

New book release by Senior Research Fellow Professor Peter Davidson

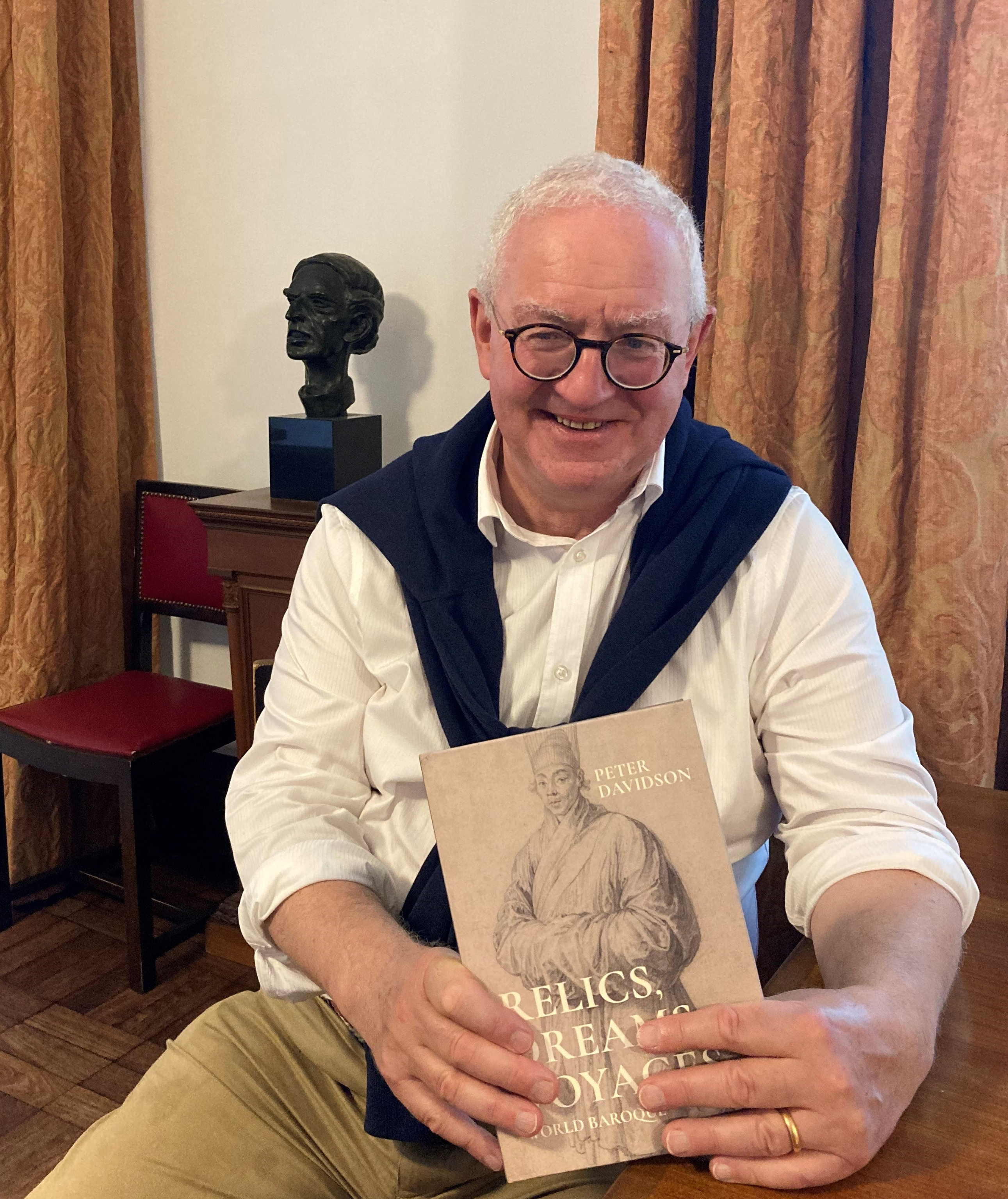

Relics, Dreams, Voyages: world baroque, is a closely focused sequence of studies of worldwide connections in all the arts in the baroque period by Professor Peter Davidson, Senior Research Fellow in Renaissance and Baroque Studies and Curator of the Campion Hall Collection

Relics, Dreams, Voyages: world baroque

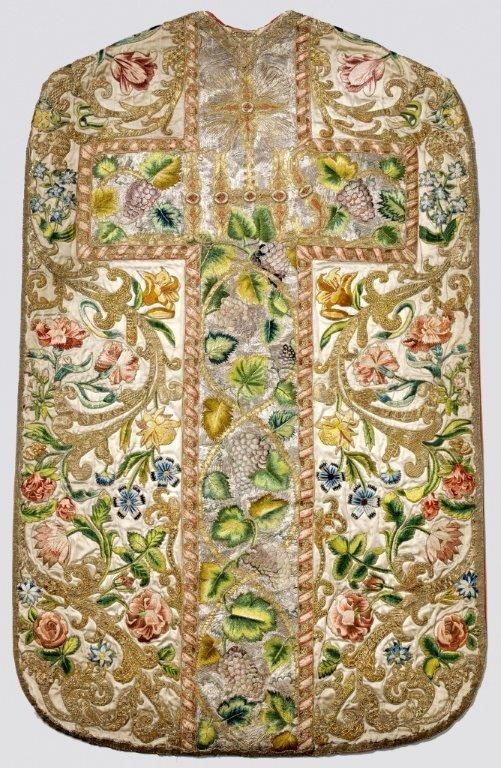

Peter Davidson’s new book Relics, Dreams, Voyages: world baroque is a collection of linked essays on connections in the baroque world, visible and invisible. There are some themes which recur: cultural hybridity, connections with the world beyond Europe, exile. This is a collection put together over twenty years and more, and is the fruit of long travels and much reading of texts lying well outside the mainstream. Much of it is concerned with people and communities in some degree invisible to mainstream Anglophone scholarship: a recurring theme o f the whole collection is the vast and assimilated Scottish diaspora, as well as the unexpected cosmopolitanism of early-modern Scotland. There are essays on garden theory imported into Scotland from France and Holland; on fantasy architecture as a consolation for Jacobite defeat; on an unpublished mid seventeenth century travel journal which documents the sheer extent of the Scottish diaspora throughout Europe. There is an essay on an exceptionally successful Scottish hitman (the one who assassinated Wallenstein) subsequently ennobled, and on the not very good painted ceilings with which he ornamented his new castle in the backwoods of Moravia, in one of which the assassination is allegorised as Theseus killing the Minotaur. In the next generation, his nephew commanded the cavalry which repulsed the Turks from Vienna, and celebrated by having the captured gold-worked banners refashioned as chapel vestments. It was by the way a descendant of this family, Charles Leslie SJ, who built the chapel of St Ignatius in St Clements’ in Oxford, the first Catholic church in Oxford since the sixteenth century.

f the whole collection is the vast and assimilated Scottish diaspora, as well as the unexpected cosmopolitanism of early-modern Scotland. There are essays on garden theory imported into Scotland from France and Holland; on fantasy architecture as a consolation for Jacobite defeat; on an unpublished mid seventeenth century travel journal which documents the sheer extent of the Scottish diaspora throughout Europe. There is an essay on an exceptionally successful Scottish hitman (the one who assassinated Wallenstein) subsequently ennobled, and on the not very good painted ceilings with which he ornamented his new castle in the backwoods of Moravia, in one of which the assassination is allegorised as Theseus killing the Minotaur. In the next generation, his nephew commanded the cavalry which repulsed the Turks from Vienna, and celebrated by having the captured gold-worked banners refashioned as chapel vestments. It was by the way a descendant of this family, Charles Leslie SJ, who built the chapel of St Ignatius in St Clements’ in Oxford, the first Catholic church in Oxford since the sixteenth century.

![[Terraced garden] The garden of the Jesuit novitiate in Rome. A space already rendered symbolic with monuments and inscriptions, is further supplied with meaning by meditation on the spiritual significance of plants, some of them brought to Rome from Jesuit missions in the East.](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Image%2022._2.jpg)

The Society of Jesus is another leading strand of the book – as perhaps the most effective global network of the baroque world, the Jesuits were vital as interpreters (in every sense), educators and collectors. A central chapter is on the Jesuits as plant collectors and gardeners. The book is introduced with a toccata or improvisation on themes of baroque connectedness: the gestural vocabulary which is common to sculpture, the Jesuit theatre, and even the whole-skeleton reliquaries of Bavarian churches; the knowledge which the Jesuit community of Antwerp, and their friend Rubens, assimilated of the Far East and the Americas – the American grain plants in the altar rails of the former Jesuit church in Antwerp, Rubens’s bird of paradise in the Adoration in the Prado. This introduction moves outwards to more mysterious assimilations and hybridities: the wonderful Goan Christian epic, the Krista Purana composed in Marathi by an English Jesuit, Thomas Stephens. (Vijay D’Souza can sing quite substantial parts of this epic from memory, and once did so for an astonished, delighted BBC production crew.) The Nativity localised in Mexico or Naples, in Latin epic and Christmas song. Even a Jesuit epic poem on the preparation and intellectual benefits of chocolate. There is a chapter on the Jesuits and the languages of Britain, which at the last ascribes an author (and a particularly interesting Jesuit author) to the four inscriptions in English, Irish, Scots and Welsh in the Basilica at Loreto, and associates him with the Welsh and Irish elements of the multi-lingual Farnese Funeral Manuscript at the Venerable English College in Rome. There is a steady focus on the British Catholic community in exile or under penalty at home: the pseudo-relics and propaganda constructed in Antwerp by the exiled servants of Mary Queen of Scots; the specifically Recusant-Catholic meanings of Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock, and indeed of Pope’s celebrated grotto at Twickenham. And there are a few chapters which can only be classified as quodlibetica – a deciphering of the iconography of an Italo-French mannerist engraving, held to be undecipherable (which it is, unless you notice the minute face hidden in the stormy sky). A meditation on artificial islands in landscape gardens, and why they are almost always associated with sadness and the deaths of friends, brings the collection to a close, and considerations of Stowe, Ermenonville and Wörlitz, also bring this collection of interlinked baroque studies perilously near to the time of the Enlightenment.

More information about Relics, dreams, voyages World baroque can be found here.

Peter Davidson reading a passage from Relics, Dreams, Voyages: world baroque.